When I started looking at the business of cultivated kelps in the US 3 years ago, demand was the big issue. Buyers didn’t know what it was, what to do with it, or how to integrate it into their products (B2B) or lives (B2C). And if they did, they thought it was too expensive to use a lot of it. So homegrown seaweeds remained a niche product, profitability a distant prospect.

After 3 years, the headlines seem to indicate nothing has changed. Soft demand saw Alaska’s harvest sag 30 percent this year to 390,000 lbs (177 tons), and it’s an open secret seaweed processors are sitting on stacks of inventory, housed in often expensive (cold) storage.

However, on a recent trip to the East Coast of the US I did see a lot of bright spots, and I will argue that the tipping point from farmed kelp over- to undersupply is closer than (at least I) previously imagined. I think cultivated seaweed on the East Coast is becoming a viable business, because

Farmers have become efficient enough

Processing bottlenecks are loosening

Nursery services are improving

The market for kelp as a hero ingredient is growing

The B2B market is finally taking off

1. Farmers have become efficient enough

It’s, as far as I know, a first in Europe and North America: seaweed farming can be profitable. Maine Aquaculture Association surveyed 16 farmers of which 9 were profitable in 2022, versus 1 in 6 in 2017. There are certainly caveats and notes in the margin, but the mere fact that profitability is now a reality for a majority of seaweed farmers (and for 5 out of 6 of the farmers growing > 75,000 lbs), is, for this author at least, a milestone. How did they do it?

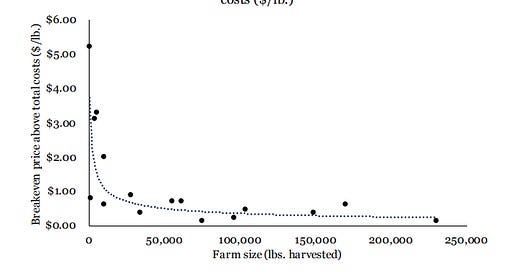

Labor efficiency improved by 1,275%: from 7.55 to 103.8 lbs (3.4 to 47 kg) harvested per hour of labor and management input. This meant that median breakeven prices dropped by 90%, from $6.89/lb to $0.66/lb (14.36 €/kg to 1.38 €/kg) for all farms, and $0.36/lb (0.75 €/kg) for farms over 75,000 lbs (34 tons).

Median yields grew from 3.3 lbs to 4.24 lbs per foot (4.9 to 6.3 kg/m), a 28% increase. In 2022, farmers received a median price of $0.60 per lb (1.25 €/kg), compared to a median price of $0.48 (1€/kg) in 2017.

It is clear that a 25% increase in farm-gate prices, a 27% increase in yield, and a 1,275% increase in labor efficiency have combined to generate much higher levels of profitability. It’s early days for the cultivated seaweed industry in Maine, so there are more strong gains to be made in years to come. But for now, seaweed farmers in Maine are efficient enough to form the foundation of a local seaweed industry that is expanding beyond wild harvests.

3 farmer quotes to put this into context:

"Tell new farming people that they can make this a part of their living. But likely not their whole living.”

“If it wasn’t for lobstering, kelp wouldn’t even be an option. Lobster pays all the bills and kelp uses the stuff we already have. If you had to go buy a boat to do this with, it wouldn't work. At least at the scale we’re at. You couldn’t make the boat payments [from kelp alone].”

“It is less costly and more profitable to go kelping than it is to go lobstering. Lobster traps this year cost more than all 3 seaweed fields put together. If anyone has an opportunity to get into this, I would jump into it. It’s only going to get better.”

2. Processing bottlenecks are loosening

Drying has been a big bottleneck for the industry. The food industry mostly wants dried kelp but existing dryers did not match the crop’s tricky requirements, leaving a market mismatch: kelp was available, but not in the form buyers wanted.

Ocean’s Balance’s new custom-made 30.000 lbs per day dryer is a big step in aligning supply and demand. It will allow the company to discontinue its frozen farmed kelp and ramp up its production of dried products including blends that sometimes include wild kelp species like dulse and Porphyra. And through its processing-as-a-service model (PaaS) the wider Maine kelp farming industry will be transformed as well. Ocean’s Balance is also bringing in a new high volume powder mill to produce a stabilizer that will grow the ingredients market.

Macro Oceans’ new reagent to stabilize seaweeds is another potential game changer. If farmers can keep their seaweeds fresh for months without a significant change in composition, storage costs will go down, processing can be spread throughout the year and wet processing for biorefining becomes a possibility. To be continued…reach out to the team if you want to learn more.

Finally, processing capacity could increase further if Greenwave’s mill-for-rent scheme takes off, growing farmers’ slice of the value pie in the process.

3. Nursery services are improving

Wild sorus collection is less reliable these days because higher ocean temperatures have reduced the stands of wild kelp: diving becomes more expensive, the sori are of lower quality. Warm waters also delay the kelp life cycle. Farmers now need to wait until December to plant, compared to October in the past, leading to a shorter growing season and lower yields.

With year-round gametophyte culture farmers can plant in October again. “The early pilot results are stunning,” says Bren Smith. “We outplanted two months earlier than previous seasons and we’re seeing twice the amount of kelp per foot than lines seeded using current industry practices.”

The other issue is supply. I was told that contamination is the biggest problem in American hatcheries, where baby kelp is quietly humming along until around about year 5, when often a sudden crash forces technicians to start from zero again.

There might be ~45 km nursery capacity in New England, which is just about enough, but there is no redundancy, so any nursery failure becomes critical.

Greenwave has teamed up with Hortimare to build a new no-glue water treatment system and a containerised nursery with 23 km capacity in an attempt to a) get one step ahead of contamination issues, and b) give farmers the opportunity to copy it and gain control over their seed supply, at the same time building more resilience in case one or more nurseries crash.

Greenwave is also trialing direct seeding. It’s one area where Europe is much further ahead, with many farms using direct seeding techniques, versus no one yet in the US.

Shopping tip: Holdfast used to be the preferred rope brand in New England, but due to high demand it has become hard to get hold off.

Greenwave is using Langman seed string now for gametophyte production: it's engineered for better gametophyte attachment and manufactured under controlled conditions, without oils and contaminants that need to be cleaned by the nursery. While Langman works well with sporophytes and gametophytes, it’s not clear if that’s true for spore seeding as well.

4. The market for kelp as a hero ingredient is growing

Food producers can integrate seaweeds in one of two ways: as a hero ingredient, prominent on the package and high in the ingredient list, or as a small “health by stealth” bonus that sneaks in some extra texture, nutrients or flavor. Since the supply chain was not ready yet for the additives market, seaweed processors turned to the hero ingredient strategy.

The challenge here is retailers’ relentless price pressure. As the most expensive ingredient, the percentage of seaweed gets pushed down, and quality suffers as a result (ever had real pesto or soy sauce? You wouldn’t even recognize it.).

Is there a middle way? The faux meat balls from chef Andrew Wilkinson of North Coast Seafoods

are delicious

contain 33% sugar kelp supplied by Atlantic Sea Farms, with green chickpeas and brown rice as a nutritious back-up

niftily avoid the retail-food service dilemma by targeting public school meals

don’t try to emulate the taste of meat, but let the kelp’s natural flavors shine instead

make school meals more nutritious

Kids love it (chef’s tip: hide the green), schools don’t mind the price, and some 35,000 lbs (16 tons) of kelp will go into the product in the next 5 months. Interest from other education departments is growing and this is a sizable market; if, for example, New York says yes, it’s a million more kids.

If you’d like to try but don’t want to be seen hanging around school cafeterias: the meat balls are based on the recipe for Atlantic Sea Farms’ new burgers, available in grocery stores across the US and the North Coast.

Snacks: while gimme seaweed sells gim sheets grown and manufactured in Korea, its success in Whole Foods, where it is now (one of) the top-selling functional snack(s), is also expanding shelf space for other, locally grown, seaweed snack brands.

5. The B2B market is finally taking off

As a new ingredient with a spotty supply chain, farmed kelp has struggled to bridge the gaps between farmers and food processors.

On top of that, post-Covid, food companies cut costs and put the brakes on product innovation.

The tide is turning. Seaweed processors in the US are getting closer to inking those long-awaited deals with larger food and pet food companies. Greenwave also noticed the market needed help. Its new Seaweed Source platform already has 444,000 pounds (200 tons) forward contracted.

While right now the ratio of additive vs hero ingredient is quite balanced, this is likely to change - soon. The scales are about to turn towards additives, in a very lopsided way.

Final thoughts: is the system diverse enough to be resilient?

Profitability is within reach for some. But will those big contracts come in fast enough for everyone to lift off before the runway ends? That remains uncertain.

While the number of off-takers is slowly growing and the applications are diversifying (cosmetics from Planet Botanicals, PFAS replacements from Everything Seaweed, sustainable rope from Viable Gear, sugar kelp biostimulant trials), the circle of companies providing farmers with seed and buying most of the kelp remains worryingly small. What if one or more falls over?

On the farmer’s side, I see a lot of diversity and resilience. Firstly, contrary to Europe where farmers rely on seaweed alone, US kelp is usually an additional crop besides oysters or lobster. Secondly, small farmers are happy to help each other out. They don’t want to protect their IP. They want to protect their lifestyle as people who make their living from the ocean.

However. The scallop farm of the Shinnecock kelp farmers died because of warming waters. Portland’s fish factories now import from Iceland because local fishermen don’t catch enough anymore; squid is migrating north but can’t be caught because quotas have not yet been adjusted. Portland’s waterfront looks towards aquaculture as its savior, but in all honesty, it’s only boat parking that’s keeping them afloat right now. So is it going to work?

It’s going to have to.

I don't see seaweed farming being sustainable as human food ingredient. OK, in Asia. But not here.

Which leaves where will the demand come from? Nutraceuticals, biostimulants, animal feed additives, bioplastics?

This is a great summary of the situation, Steven. It seems things are destined for slow, steady growth given the interdependence of seed availability, farm capacity, processing capacity, and markets. A rapid expansion of one of these building blocks is possible, but not economical, so all have to grow together.

Not mentioned was the farm leasing conundrum and the logjams that have been experienced in nearly all permitting jurisdictions. In order to expand production, growers may find it easier to amend existing leases rather than establishing new acreage. New farm equipment designs with closely spaced, pretensioned growlines can expand a farm’s potential tenfold while providing reduced capital costs per foot of growline.