What’s the outlook for carrageenan?

It’ll probably keep chugging along at 1-2% for the foreseeable future, but supply risks are rising

While there is innovation in applications for tropical seaweeds (sea moss, biostimulants, textiles, pet food, aquafeed, bioplastics and (dare I say it?) biofuels), carrageenan and agar remain the two biggest markets for seaweed farmers in warm waters as of right now.

1. Demand

1999 - 2024

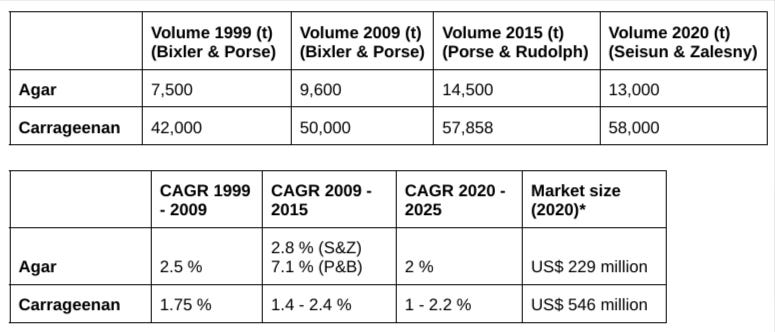

Between 1999 and 2024, the carrageenan industry chugged along at an estimated average annual growth rate between 1 and 2 percent. Market size was estimated at $546 million for 2020 by Seisun & Zalesny, excluding China, and $600-700 million worldwide for 2016 by Campbell & Hotchkiss. A guesstimate average based on this data would put the market value of the carrageenan market in 2024, including China, at around $735 million.

For the past 20 years, the Cornucopia Institute and researcher Joanne Tobacman have been the driving force behind a campaign to push carrageenan out of the American consumer market. According to Cornucopia, carrageenan causes cancer. According to the industry, it doesn’t (while under their breath accusing Cornucopia of being secretly funded by the lobbies of replacement gums). Who is right? The food authorities of the US, EU and the rest of the world have so far not found any reason for concern.

Nonetheless, Cornucopia’s campaign has been effective to a certain extent, with premium brands of ice cream and pet foods switching over to other gums like agar or pectin as a form of risk management. More importantly, consumers’ preference for labels that are “lean and clean”, along with a desire from industry to have less waste and more environmentally-friendly processing have spurred on the development of functional food fibers.

Holistically processed, they have improved binding and gelling properties to regular fibers, although usually not to the same extent as the hydrocolloids they are replacing. But they have far better names than their hydrocolloid cousins. “Fermented whey extract” sounds healthier than xanthan gum; pectin becomes the friendlier “citrus fiber”. We covered seaweed fiber examples in last week’s newsletter, here are some more: Sea Veg Fibre, Ceamsea.

Over 80% of the global carrageenan production goes into three applications: processed meats, dairy and desserts/jellies (pet food, toothpaste and beer cover another 15%). The major growth engine for carrageenan in the past 25 years has been China, where consumption of processed meat and dairy products has grown steadily since the late nineties as hundreds of millions of people urbanized, entered the middle class and acquired diabetes.

2025 - 2050

While there are still plenty of Chinese wannabe jelly munchers left to join, India is now the world’s biggest source of new consumers, forecast to add 47 million first-time ice cream biters in 2025, compared to China’s 30 million untrained yogurt slurpers. In the next 25 years, 600 million Indians will go from dog kicker to dog spoiler. Notwithstanding other fast-developing countries with big populations like Indonesia, growth in carrageenan will be driven first and foremost by India.

Meanwhile, in Europe and the US, the concern over ultraprocessed foods along with slowly declining meat consumption and production could see demand soften gradually.

Although academic research has brought to light some new use cases in medicine, soil improvement, construction and bioremediation, none of this has been commercialized. Bioplastics? The frontrunners prefer to work with agar, raw seaweeds or processing sidestreams. The lack of innovation opens carrageenan up to attacks from competing hydrocolloids, functional fibers and new techniques and products that avoid hydrocolloids altogether.

Having said that, carrageenan remains a powerful ingredient, and it stays on the organics list (even though inorganic fertilizers are sometimes used) because there is no organic replacement yet for some use cases. However, without innovation carrageenan could be surpassed or made redundant. For now, though, it has its place.

Putting it all together, we surmise that the next 25 years might look a lot like the past 25 years in carrageenan consumption: a 1-2% yearly growth rate driven by the rise of the Asian middle class. That would make it a market worth slightly over $1 billion in 2050.

2. Producers

There’s the Americans (Cargill, CP Kelco, IFF), the Filipinos (W, Marcel, Shemberg, TBK), the Chinese (BLG, GreenFresh, Longrun-Newstar), the Indonesians (too many to mention) and the rest of the world (SELT, Farmesa, Gelymar, Ceamsa).

Do they all make carrageenan? Some have gotten out of the game. The real money is in blending and marketing specialty applications to your customers. You get the basic carrageenans from whomever is cheapest and blend together the different grades along with other hydrocolloids to your customers’ requirements. While the former often still looks like an industrialized version of cooking a stew, the latter requires more lab and sales people with strong technical knowledge and skills.

Now, despite the variety on offer, if you take a trip to Indonesia, there is only one company that people want to talk to you about: BLG. Run by the shadowy Mr Wang, it dominates the business. It is said that nobody really knows how much seaweed Indonesia produces, but Mr Wang knows, down to the last kilo. Local traders are being pushed out as BLG is sending employees to the islands with suitcases of money, tallying the numbers in the most remote locations.

Might that be a good thing - back to the old days of the integrated company model? Isn’t it those pesky middlemen who are always sending the price up and down with their speculation, causing havoc in the market?

No. The price for raw dried seaweed is set by BLG and GreenFresh. According to science, the price oscillates because of seasonality, as well as ‘campaign buying’, buying a lot when the seaweed is plenty and the price is low. According to locals, it has more to do with the age-old practice of ‘fucking each other over’, artificially pushing the price up whenever news arrives of a competitor getting a big order.

Is that then also why it’s only the price of cottoni that fluctuates, and spinosum is stable? That’s correct; the market for iota carrageenan from spinosum is small with less competition and fewer applications (mainly toothpaste). Not worth fighting over.

3. Production models

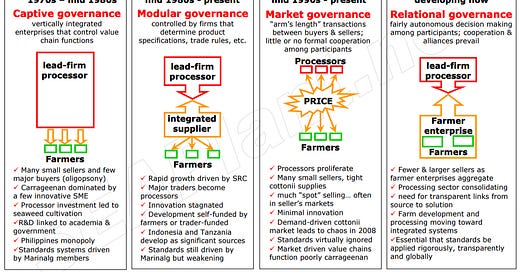

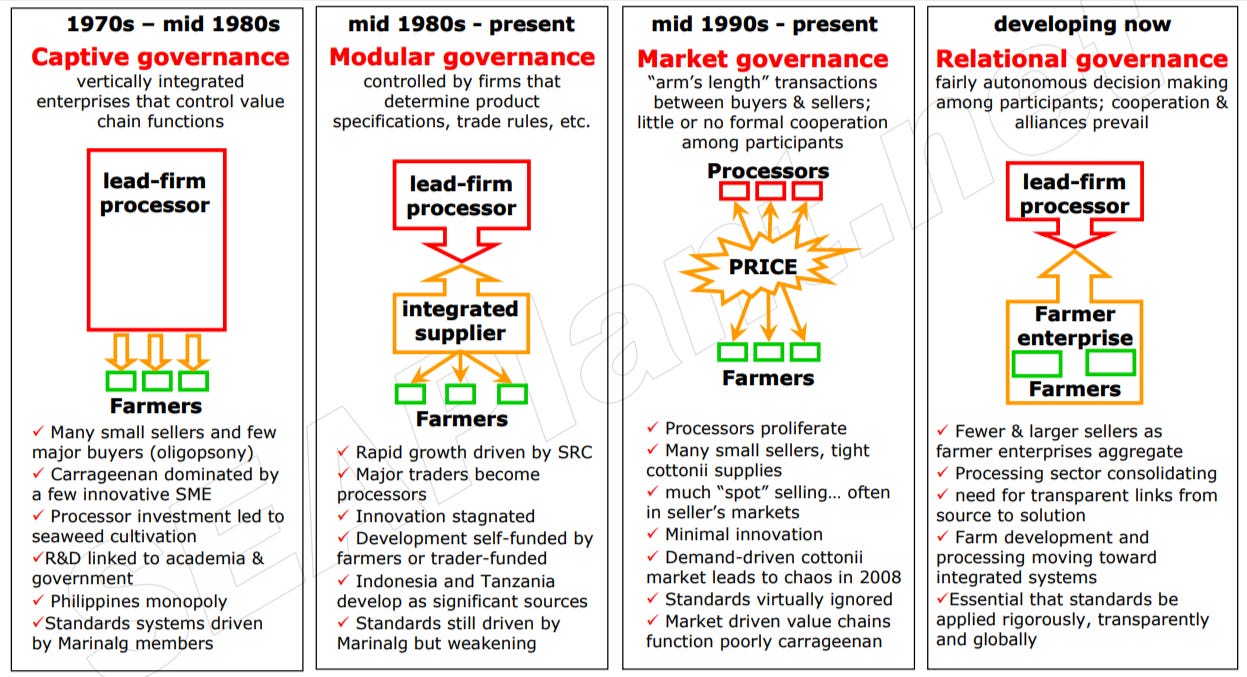

As the twenty-first century commenced it became clear to many in business, government and aid that something was broken in seaweed-to-hydrocolloid value chains. There was a need to move towards integrated aquaculture, new cultivars, multi-stream processing, new markets and relational governance.

That last paragraph was written fifteen years ago. So far, not much has happened. It’s nearly 2025 and relational governance (Coast4C, Ocean Farmers, SeaKITS, Banyu) is still just developing. Same for new markets and multi-stream processing (biorefining these days). And little progress has been made so far on new cultivars and integrated aquaculture.

4. Raw materials

Risk of supply disruptions is growing: carrageenan content in seaweeds continues to go down and seaweeds, especially Kappaphycus alvarezii, are quicker to fall victim to ice-ice disease, pushing farmers to use fertilizers to keep growing. Might seaweeds be on the cusp of their own ‘banana moment’?

What about the workforce? On my travels through the tropics I have found that there are still plenty of people who are happy to work for the money that seaweeds can bring. But they are getting older. The average farmer’s age is 55 in Indonesia and 58 in the Philippines. 65% of farmers don’t want their children to follow in their footsteps. Fishermen are a bit younger, but half are already over 50. Old enough to inspire food security worries.

What’s next? Although I always advocate for humanity to accept defeat and go gracefully, some just don’t want to hear it. So they are working on solutions. Mechanization is coming. New cultivars are being tested, aided by the Forjazul platform and its genome sequencing project, as well as work at Chinese institutes like BGI and Xiamen U.

The persistent issue of low quality/quantity of seedstock is being tackled by local governments and social enterprises. Is tissue culture the way forward here? That seems to be an ongoing debate.

Are GMOs necessary to ward off the effects of climate change? Some argue what is needed instead is a return to the basics of traditional dedicated observation. A tropical seaweed resilience institute has been established, but without the necessary funding, it will remain an empty box.

5. Indonesia

In the past decade, all three major Chinese seaweed companies have established a factory in Indonesia. Has this been a boon for Indonesia? Zhang et al explain that, on the plus side, the investments have created hundreds of jobs, mostly for local Indonesians, and put upward pressure on seaweed prices.

On the negative side, they are exporting pollution, as Indonesian rules are laxer than China’s and easier to ignore. And they are putting Indonesian companies out of business. That’s on the one hand because Chinese companies are better capitalized and have access to harder-working, higher-skilled workers. But more importantly, it’s because they get strong tax advantages from both the Chinese and Indonesian governments.

The Chinese state refunds the 13% VAT for carrageenan exports of its companies. From the Indonesian state, BLG receives exemption from import tariffs, VAT and excise duties, as well as simplification in the import of inputs like machinery and chemicals.

Zhang et al conclude that “Indonesian government agencies, at all levels, may wish to impose tax, technology transfer and environmental terms that more directly benefit Indonesia.” Anyone familiar with the moral compass of Indonesian politicians knows not to keep their hopes up.

The Philippines processes all its own seaweed, even importing seaweeds (and ATC) from Indonesia. Can Indonesia also exit China’s warm embrace and stop sending its raw dried seaweeds overseas?

Not any time soon. Export restrictions for seaweeds have been shown to be a bad deal for seaweed farmers (customs officials benefit though). Indonesia produces more seaweeds than it can process itself, and while there are some skilled industrious people for hire, there aren’t nearly enough of them for Indonesian companies to break into new markets en masse.

Indonesian seaweed is tightly linked with China culturally, as all Indonesian carrageenan companies, and the majority of trading outfits, are owned by Chinese Indonesian families. Can India, with its strong STEM skills, shared Hindu and Muslim heritage and similar country name, form a counterweight?

Talking to traders, it’s clear that demand for raw dried seaweeds from India is growing. Will it be enough to balance Chinese dominance? That remains to be seen.

Steven, my compliments. You did a great job. Greetings, Paul Robert van der Heijden