How much are kelp forests worth? $500 billion a year, according to the latest conservative estimate.

Kelp forests have been in decline for the last 50 years, though restoration efforts are underway. Can these underwater forests be saved and strengthened with interventions and new forms of finance that leverage and value their ecosystem services, or will the effects of climate change greatly diminish their presence in our oceans?

Carbon debates

Kelp have suffered widespread losses across much of their range, at a global rate of decline of 1.8 per cent per year, with at least 1.5 million hectares being lost this century alone. Climate change, poor water quality and overfishing are the primary causes for the decline.

Into the Blue, UNEP’s recent global synthesis report on kelp forests, lays out a two-pronged strategy to contain the losses. One focus is increased data gathering, especially from less-studied areas of the ocean. The other side is political: amid a call for expanded partnerships and a holistic approach with kelp at the center, the report recommends to incentivize protection through the use of blue carbon credits.

Before blue carbon credits for kelp forests can become a credible source of conservation revenue, though, we need more answers.

Can human interventions to kelp forests generate sequestration of a meaningful magnitude? And can robust methodologies and frameworks to measure, report, and verify sequestration generated by these actions be developed?

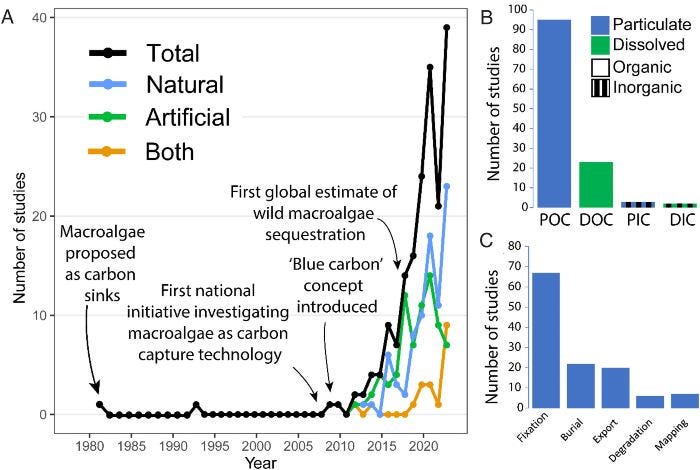

Pessarrodona et al. took an important step in July, distilling the current state of knowledge from over 180 papers and pointing out the key gaps that still need to be resolved, for instance around less-understood sequestration pathways like the air–sea CO2 flux, or emissions of methane and nitrous oxide that remain poorly quantified.

Nevertheless, the authors conclude that the protection, restoration and improved management of kelp and seaweed forests globally could provide mitigation benefits in the range of 36 million tons of CO2, equivalent to the CO2 capturing capacity of 1.1 to 1.6 billion trees, particularly in temperate regions where nutrient-rich waters support the tallest forest growth.

As a result, polar and temperate countries that have yet to engage in blue carbon solutions may soon have the opportunity to do so – for instance, the study identifies the ‘Great Southern Reef’ along the Australian coastline and the underwater forests of Eastern Canadian Arctic, Norway, Chile and Japan as areas with high carbon sequestration potential.

*** EABA is hosting a workshop on algae and carbon on September 19 in Brussels. See you there? ***

Restoration efforts

In Catalunya, the Marine Forest Team has reintroduced a species of Cystoseira, Gongolaria barbata, that disappeared from the area 40 years ago. In the Adriatic, the first experiment to restore the endemic stands of Fucus virsoides were successful.

On Prince Edward Island, Canada, a unique species of Irish Moss is coming back from the brink of extinction due to the work of dedicated conservationists.

After the success of early efforts to save the giant kelp forests of Tasmania, a new project will expand restoration efforts, involving The Nature Conservancy, CSIRO and various Australian universities.

In Portugal, Seaforester shared a beautiful video about their failures with the spore bag technique and their success thus far with green gravel.

Ocean Wise’s restoration plans hope to deliver at least 5,000 hectares of afforested kelp in British Columbia, and Chile by 2025.

In China, the government looks toward its strategy of massive scale marine ranching, building artificial reefs and planting algae and seagrass beds. Carbon is not a consideration here: the goal is to improve profits by increasing fishery stocks, improving conditions for aquaculture and opening up tourism opportunities. Can China put the environment first?

In the US, bull kelp will not be put on the endangered species list by NOAA after all. Good news for those making a living harvesting wild bull kelp. Meanwhile, scientists in B.C., Canada, are racing against the clock to biobank some of the diversity of Canada’s bull kelp.

In Norway, sugar kelp forests are on the Red List, and now also on the Norwegian Environmental Agency’s Rescue List.

To sum up: despite recent promising results, the nearly 15,000 ha of seaweed habitat restored so far are still a long way off from the 1 million ha by 2040 goal post set by the Kelp Forest alliance. Restoration remains costly and small-scale. Preventing losses should remain the first option.

Urchin harvesting

Urchin ranching, the technique where kelp-eating zombie urchins are harvested, then fattened up on-land before being brought to market, is getting more popular. Building on the success of pioneer Urchinomics, new companies are popping up, like Seabed Innovation (Norway) and Aristotle’s Lantern (US).

Urchinomics itself is building joint ventures to expand to Hong Kong (Regenerative Solutions) and New Zealand (Kinanomics).

Marauder Robotics is building an urchin removal robot, while Ocean Soteria is working on an autonomous subsea floor crawler that culls zombie urchins by punching a hole in them.

Kita-Sanriku Factory is a Japanese urchin ranching company that is now investing in Australia. Theirs is a different model that does not have the same benefits for the kelp, though. KSF does not harvest zombie urchins, but instead hatches baby sea urchins on land and raises them in tanks for a year before releasing them into the ocean to mature.