In the past few decades, green tides of different species of Ulva (sea lettuce) have choked up beaches from the Yellow Sea to the Baltic, and from South Africa to the Mediterranean.

Too much Ulva. Way too much. And yet, paradoxically, there isn’t enough. Or at least, there is not enough steady, high-quality supply at the right price for food, feed and biostimulant producers to rely on.

It is something that everyone who plans to harvest harmful algal blooms will have to confront sooner or later. The timing, quantity and location of the blooms is often hard to predict. For a steady, high-quality supply, some cultivation needs to be added. If growing some Ulva yourself is what you plan to do, keep an eye out for the SeaWheat project, which will be digging into exactly this topic for the next 4 years.

Ulva news

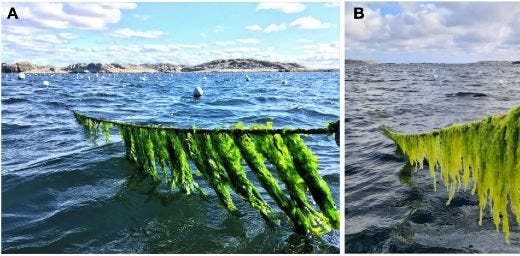

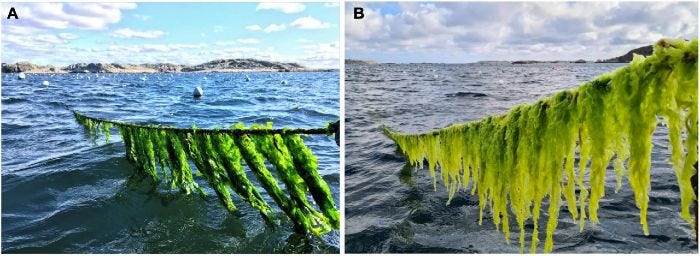

In Sweden this spring, Nordic Seafarm harvested the world’s first ton of at-sea cultivated Ulva, building on work by Sophie Steinhagen et al. at the university of Gothenburg. Meanwhile in Portugal, Easy Harvest is piloting mechanical harvest of Ulva and Asparagopsis blooms from the Algarve coast.

In southern Spain, Mediterranean Algae is raising money (ES) to expand its Ulva production for use in cosmetics, food and biostimulants, while the Dutch government is supporting onshore Ulva cultivation with a 3 million euro grant.

And in New Zealand, a license has been granted to the University of Waikato and WaikatoLink for the country’s first commercial land-based seaweed farm. Waikato is also where the pilot for Aqua Curo is taking place. Aqua Curo is looking at Ulva as a bioremediator to filter municipal wastewater and valorize the nutrients, as pioneered by Pacific Bio in Australia.

Upping the protein levels

Biorefinery startup Oceanium has received a third IUK Smart Grant, this one to develop functional protein from Ulva blooms and cultivated kelp. The relatively high protein content in Ulva has long been touted as a future feed and food solution. Feed it to fish, for example.

Or abalone.

South Africa has become the biggest producer of abalone outside of Asia, with 12 land-based farms producing some 2000 ton per year. The main ingredients in their abalone feed are fish and soy meal. For both economic and ecological reasons, it would be good to switch them out.

As part of the AquaVitae project, MariFeed added Ulva to their feed pellet, and saw excellent results on feed conversion and growth rate.

Not too surprising, really, considering South African abalone farms already grow quite a bit of Ulva. It helps clean up the abalone’s wastewater, and they can feed it right back to the hungry gastropods. A great circular system, at first glance. Not so sustainable on second glance, though, since chemical fertilizers are added to turbocharge Ulva growth.

That has to change. And it might. Early trial results (no papers out yet) suggest that adding seaweed-based biostimulant raises the protein levels of the Ulva considerably. That would be better for the ocean, and it makes for happy, fat abalone (and Chinese end-customers).

Fun fact: feeding the abalone a bit of Gracilaria makes their flesh taste sweeter and more umami, while simultaneously giving their shell the red color so prized in China.

Are we really going to grow seaweed in offshore wind farms?

I don’t know. After speaking to a major wind farm developer, the answer seems to be: no. It’s not economically viable according to him, and neither is floating solar, tidal energy or any other type of aquaculture within wind farms.

But when I read Professor De Clerck (NL), I suddenly become hopeful that it could become viable, given another 8 years of research. The first harvest from their offshore pilot is in, but a lot more needs to be done.

Two new grants will help fill in the blanks. A Norwegian-led consortium has received a 7 million euro grant to research wind-aquaculture co-location and artificial reefs. And SeaGrown has received a 2.8 million pound grant to further develop their concept of mechanized offshore seaweed farming off Britain’s east coast.

Asparagopsis expansion

Curious coincidence, or a new trend? Both CH4 Global and Blue Ocean Barns announced in the past weeks that they started partnerships with other producers to expedite the growth of Asparagopsis beyond their own farms. CH4 Global will establish production in an IMTA system with kingfish producer Clean Seas, while Blue Evolution will help scale up production for Blue Ocean Barns.

More algae news

Do you want more seaweed and algae news? Sure you do. Have a look at the Paxtier newsletter, which does a good job summarizing both micro- and macroalgae news, on a weekly basis.