Seaweed nanocellulose opens new markets

Also: New Zealand’s rimurimu strategy, latest carbon science, my opinion on seaweed sinking

Last month, Aotearoa New Zealand saw the first large-scale outplanting of hatchery grown native Ecklonia radiata seaweed, with 228 metres of tiny seedlings planted in the waters. It will take time for the 3-year, NZ$5 million pilot to bear fruit, but this is by no means a random idea.

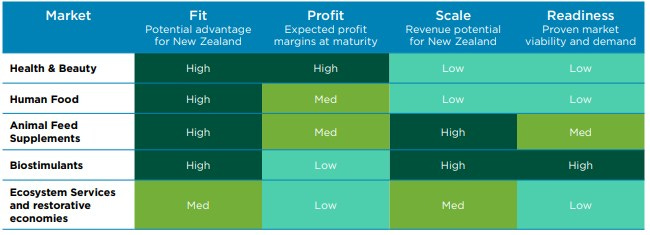

Starting from market demand and working its way backwards, the Aotearoa New Zealand Seaweed Sector Framework methodically lays out a way forward for the country’s rimurimu industry: which species have high potential for which applications, where the gaps in the supply chain are, where the risks lie, etc. It’s a very clear road map, explained in detail at the first Seaweed Summit.

Bren Smith adds: “I love how the framework allows you to see the whole capital stack. Because there is no way you can do something as complicated as agriculture without at least six different types of capital, right? So the framework lays out this capital strategy, without spelling it out explicitly.”

The pilot focuses on Ecklonia radiata, because this is the species New Zealand’s seaweed pioneers AgriSea have been using for the past 25 years. Besides the more common uses in biostimulants and animal feed additives, the company has developed an interesting niche in bee nutrition as well as an Ecklonia beverage.

Nanocellulose developments

AgriSea is now cutting all kinds of edges with their plan to produce nanocellulose hydrogel from their Ecklonia and Undaria waste streams. Nanocellulose is a pseudo-plastic with some pretty amazing properties; it has applications in almost everything, from oil spill cleanups over car manufacturing to adult diapers. It is usually made from wood pulp, with Japan a major leader in the field.

The cellulose in seaweed differs from what you find in trees and other terrestrial plants. It forms chains up to four times wider, which allows for interesting new functionalities. AgriSea will start off using it in their skincare range Ocean Organics.

Potential competitors in seaweed nanocellulose are Everything Seaweed, which plans a similar operation in Iceland, and Borregaard, a producer of wood pulp nanocellulose and a major shareholder in seaweed biorefinery Alginor.

New seaweed carbon science

It hasn’t been that long since our last seaweed for carbon science round-up, but carbon remains a topic du jour and interesting new papers keep coming up.

Hasselström and Thomas took a critical look at seaweed LCA’s and concluded: “The sector has potential to contribute to climate change mitigation, though the evidence for this across the whole life cycle remains quite thin to date, especially relative to the hopes that are pinned upon it as a nature-based climate solution.”

Williamson and Gattuso leave even less to the imagination in their paper’s title: Carbon Removal Using Coastal Blue Carbon Ecosystems Is Uncertain and Unreliable, With Questionable Climatic Cost-Effectiveness, making it "premature to operationalize marketable blue carbon". Therefore, while restoring blue carbon ecosystems has many environmental benefits, "restoration should be in addition to, not as a substitute for, near-total emission reductions." Seaweed is not mentioned but many of these arguments could be said to also apply to kelp forest restoration.

On top of that, warmer oceans may limit kelp forests’ potential to store carbon for long periods of time (explainer - paper).

Notwithstanding the critical remarks above, The Seaweed Company started selling carbon credits last week through Climate Cleanup’s new ONCRA mechanism. The credits are not based on seaweed cultivation, but rather on the ability of their biostimulant to add more carbon to agricultural soils.

Is this a valid additional source of revenue that will be taken up by biostimulant producers the world over in years to come? Or rather a well-intentioned idea soon to be discredited? I guess we’ll have to wait to find out.

Opinion: a seaweed sinking ban is premature

Sinking seaweed to prevent it from suffocating fragile Caribbean ecosystems and economies has received widespread criticism from within the seaweed and ocean communities. It is obviously a very emotional subject when people who usually advocate for science to drive the debate, suddenly start ranting in all caps. SAY NO TO SEAWEED SINKING! HELP US TO STOP THIS MADNESS!, wrote seaweed pundit Pierre Erwes.

What am I missing here?

Beyond a small number of modeling studies, both the environmental impacts and the effectiveness of the idea at climate-relevant scales remains largely unresearched; Ocean Visions’ recently released seaweed sinking research framework outlines the many research gaps that still need to be answered before anyone can say with confidence whether sinking seaweed is a good or bad idea.

In other words, unless the marine scientists at Ocean Visions are profoundly mistaken, a ban on sinking seaweed as advocated by Pierre Erwes is not backed by science. A moratorium to thoughtfully assess the full impact before proceeding, similar to the one proposed for deep-sea mining by Sylvia Earle and Daniel Kammen, seems to make more sense to me in that case.

Beyond the main argument of the impacts on deep ocean ecosystems and ocean productivity (which, as argued above, are unknown), the other common argument against sinking is that seaweeds are too useful to sink.

However, in the case of the 20 million tonnes of Sargassum that washed up on Caribbean beaches this year, it should be clear by now that it is not a biomass that’s easy to valorize (due to high arsenic loads, among other things), and that it will take decades of work and billions of dollars of investment to build up an industry large enough to deal with the biblical size of the problem.

So why deny the populations of the Caribbean (and future generations dealing with harmful algal blooms in other parts of the globe) the chance to find out if sinking seaweed in eg. anoxic basins - which do not contain eukaryotic life and preserve more than 90% of carbon deposited for thousands of years - is an environmentally safe possibility that can preserve their island economies and ecosystems while value addition ramps up?

If it is damaging to the environment or economically unfeasible, well, that will be great to know - let’s definitely not do it then. But unless I have missed some crucial papers, it feels to me like it’s too soon to rule out the possibility. Do correct me if I am wrong.

But not in all caps, please.