Chile: wild harvest champion bucks the global seaweed trend

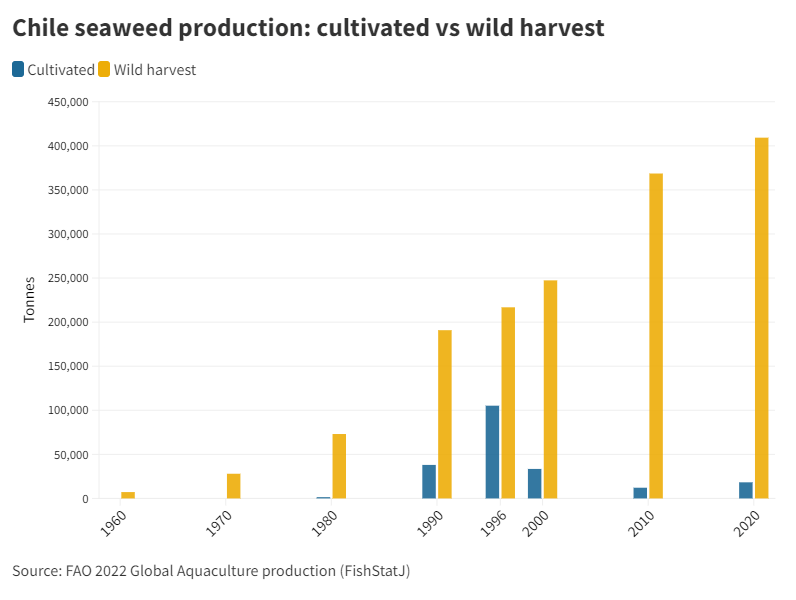

Wild harvests continue to grow while cultivation has seen a precipitous decline.

The global trend in the seaweed industry over the past 50 years has been for wild harvests to remain small but stable, while cultivation grew tremendously. Not so in Chile.

Chile’s wild harvesting sector has continued to grow. It has now become the biggest wild harvester in the world (according to FAO data), producing more than 400,000 tons in 2020, double that of nearest pursuers China (220,000 t) and Norway (150,000 t).

Meanwhile, cultivation has withered. After a promising start in the 1980s, cultivation of Gracilaria chilensis (the only species currently grown in Chile) hit a peak of 105,000 tons in 1996. By the end of the decade, just 30,000 tons remained.

Let’s unpack this graph.

Why did seaweed cultivation in Chile decline?

In a word: profitability. Cultivation in Chile needs higher prices, higher productivity, more value add and better regulation if it wants to turn a profit and stay in business.

Higher prices: demand for Chilean seaweeds increased in the past few decades, but this has not led to higher prices because the response from fishermen has always been to simply harvest more from the seabed. They expanded supply, which kept prices low.

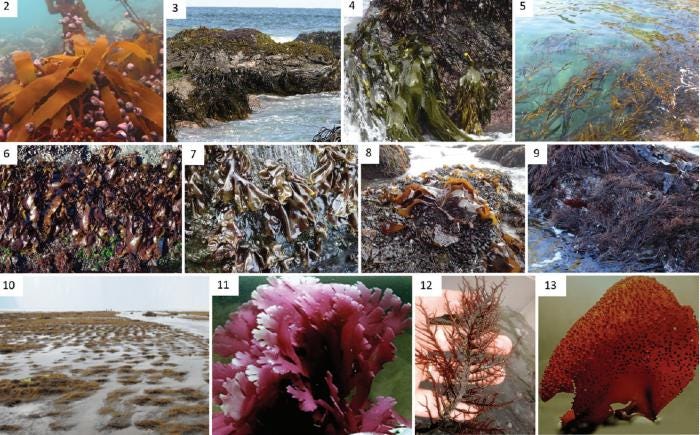

Higher productivity: scientists have figured out how to grow many of the species currently harvested in Chile: Gigartina skottsbergii, Sarcothalia crispata, Callophyllis variegata, Chondrachanthus chamissoi, Macrocystis pyrifera and different species of Lessonia and Gelidium.

However, more efficient production methods and higher-yielding strains are needed to improve mariculture’s competitiveness vis-à-vis wild harvest. Other vexing issues weighing on productivity are pest control and a lack of diligent farming practices.

More value add: Chile mainly produces seaweeds for the food and hydrocolloid sector (agar, carrageenan, alginates), with most of it exported as raw biomass to China. A viable seaweed sector will need to add more value by aiming for higher-end markets and, in the longer term, employing a biorefinery strategy to maximize the value of the biomass.

Better regulation: A sea space license fee is set at a fixed price, but this is cut to the size of Chile’s more profitable salmon farms.

Better enforcement of wild harvesting quotas will lead to higher prices. Keeping new introductions out is another challenge.

Is the growth of Chile’s wild harvests sustainable?

No. Currently, regulations for sustainable exploitation of seaweeds are only present in the north of the country. In the south of the country, extraction is allowed without any management plan. Decreases in biomass stock, density and adult populations have been observed in both north and south.

Authors debate the effectiveness of the government’s management plans. Some say it partly works, but there are serious issues with enforcement. Others say it only serves to legitimize overharvesting and the exploitation of those at the bottom of the pyramid, and the best way to reduce overharvesting is by limiting exports.

I follow Berrios et al. who argue that management is highly complex and only with systemic changes and an integrated approach the issue stands any chance of being resolved.

In the meantime, Chilean police are focusing their efforts on the traders trafficking the illegally harvested algae.

Meanwhile, in Peru

Besides Chile and Brazil (where Lithotamnium is harvested), Peru is the only other major seaweed harvester in South America. Peru produced some 45,000 tons of mainly Macrocystis and Lessonia in 2022 (as per government data), 90% of which goes for export to China.

It’s a new business for Peru that has sprung up in the past 15 years because of increased demand from China on the one hand, and better access roads to areas that were previously too remote for profitable extraction.

Laws are strict but enforcement is almost non-existent, leaving the kelp forests in a very bad state. Last year’s massive oil spill hasn’t helped either.

On a positive note: Argentina

At the end of 2022, lawmakers in Argentina unanimously approved a law to create a 485,000 hectare (1.2-million-acre) protected area in Peninsula Mitre at the easternmost tip of the Tierra del Fuego Province. The region is Argentina’s biggest carbon sink (it has one of the largest peat reserves of South America) and is home to 30% of Argentina's kelp forests.

The kelp forests here are pristine and have shown unusual stability for the last 200 years due to frequent marine cold spells from glacial melting. No marine heat waves have been recorded in the area since 1984.

The outlook for these kelp forests looks ok for the immediate future. Current climate and ocean models predict the Southern Ocean will avoid warming dramatically. This in itself brings along other problems for the ecosystem, but let’s keep at least one paragraph positive.

The people of Argentina are doing more. In Chubut, the populations of wild Gracilaria declined in previous decades owing to overharvesting, oil spills and invasives. Rewilding Argentina is trying to bring them back.

Thanks for reading Phyconomy! You can now support this newsletter (with money - one-time or monthly) through the button below, if you feel like it.